Mary Shelley's Actual Frankenstein

“Frankenstein is universally known; & though it can never be a book for vulgar reading,

is everywhere respected.”—Sir Walter Scott, 1823

Molly Dwyer's award-winning novel on the life of Mary Shelley was released on February 29, 2008, one hundred and ninety years after Frankenstein, the debut novel of nineteen-year-old Mary Shelley, was published anonymously (on January 1, 1818).

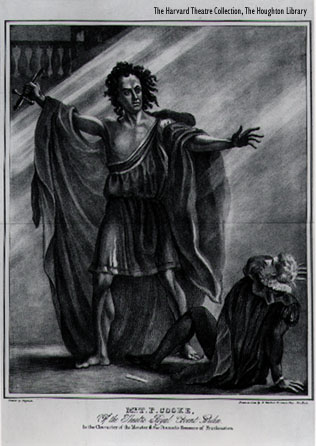

Frankenstein caused a stir from the moment of its release. It became famous, however, when it was turned into a stage production. The playbill (left) is from the first London performance in 1822. And Frankenstein continues to fascinate. Its latest manifestation, Mel Brook's new Broadway musical came out in the fall of 2007. Young Frankenstein gives but a nod to Mary Shelley's plot, which is not unusual.

Each telling of Frankenstein—from London's 1822 performance, to Hollywood's first Frankenstein in 1931, to Mel Brooks films and now his musical, even Branagh's 1994, Mary Shelley's Frankenstein—has transformed the tale into something other than the original, making Mary Shelley's actual Frankenstein one of the most recognized, but unknown stories of all time.

Requiem for the Author of Frankenstein addresses the fact that Frankenstein was written by a precocious 19-year-old who happened to be the daughter of two republican radicals. She also happened to be living out of wedlock with Percy Bysshe Shelley, a young man who was so radical in his politics he was in danger of arrest, and under the influence of Lord Byron, yet another radical who had fled England.

Anna Trevor, Requiem’s contemporary protagonist, has been invited to present a paper on Frankenstein at the Chawton House Centre for the Study of Early English Women's Writing. Anna developed a controversial theory that Frankenstein addresses the role of women and is consciously political, a satire not unlike Orwell’s Animal Farm, or Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five.

“Victor Frankenstein,” says Anna, “is filled with good intentions, and in the beginning seems to fit all our expectations for a hero. We soon see, however, that he is dangerously ignorant. No knight in shining armor returning order to the world, Victor is an ineffectual, self-absorbed coward who cannot acknowledge responsibility for the monster he has created. He cannot admit his trespass. Filled with naive and enthusiastic hubris, Victor is incapable of recognizing, let alone scrutinizing, the implications of his actions. He is too entangled and entrenched in his narcissistic delusions of grandeur. He unquestioningly accepts the cultural norms—norms that elevate the male above the rest of humanity, and the human above the rest of creation; norms that fail to realize the magnificence of Earth and its life processes or of the cosmos that gave rise to the Earth, to humanity, and indeed, to Victor himself.”

“The women in Frankenstein,” she goes on to say, “are alarmingly domestic, absolutely selfless, and ultimately, utterly useless. Mrs. Shelley's portrayal is purposeful. Her vacant females dramatically demonstrate the nineteenth–century masculine ideal of perfect femininity: they are sweet, endearing, ever-giving and soothing, empty-headed and childish, unquestioningly cooperative, pathologically passive, fundamentally victimized, and thoroughly domesticated. In fact, they die, completely unrealized, destroyed by the culture they so ignorantly and hopefully embrace, victims of the imbalances brought about by an unchallenged masculine ascendancy.

No matter how perfectly (or imperfectly) the women in Frankenstein manifest the desired feminine stereotype, they meet the same fate, dying prematurely, while helplessly invested in a set of cultural norms that leave them utterly disempowered. Although Frankenstein is usually characterized as a gothic romance, it is more appropriately understood as satire that exposes and ridicules the cultural imbalance between the masculine and feminine. Mrs. Shelley has magnified the preposterous implications of a world in which only males act as thinking agents—indeed Victor, in creating life alone, is rendering the feminine irrelevant.

Mrs. Shelley is using the time-honored literary device of satire to expose human and institutional failings, and the dangers inherent in perpetuating them. One would hope that the magnification will cause society to examine its presumptions, and change. It is interesting to note that from the time of its publication, Frankenstein was fashionable reading, and quickly became, even in Mary Shelley's lifetime, a popular stage production. From the beginning, however, Frankenstein's interpreters, like those who produced film versions in the twentieth century, were men who consistently presented Frankenstein as a somewhat farcical horror story. These interpreters missed the point; Frankenstein is a critique of gender imbalance. The defining genius of Frankenstein is its portrayal of the feminine in ironic caricature.”

While there's nothing wrong with taking the politics out of political satire, and turning it into comedy, gothic horror, or even a jaunty musical, it seems appropriate that on the eve of Frankenstein's bicentennial, we begin to look at the truth of what this book is about. Requiem for the Author of Frankenstein does just that, bringing a new perspective to the table, a framing of the tale that is both valid and valuable in our modern, troubled world.